Climate - truthful information about climate, related activism and politics.

6369 readers

534 users here now

Discussion of climate, how it is changing, activism around that, the politics, and the energy systems change we need in order to stabilize things.

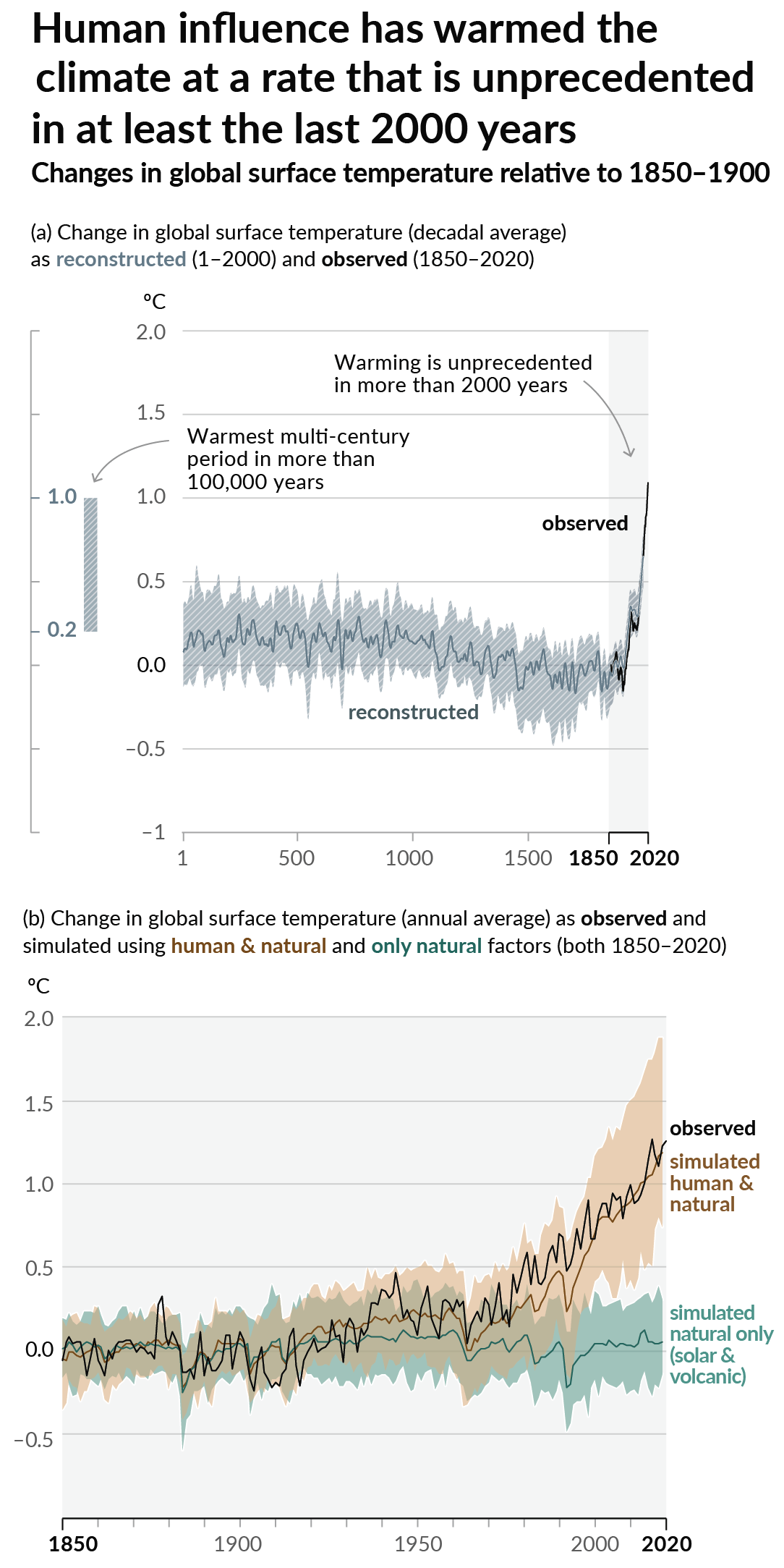

As a starting point, the burning of fossil fuels, and to a lesser extent deforestation and release of methane are responsible for the warming in recent decades:

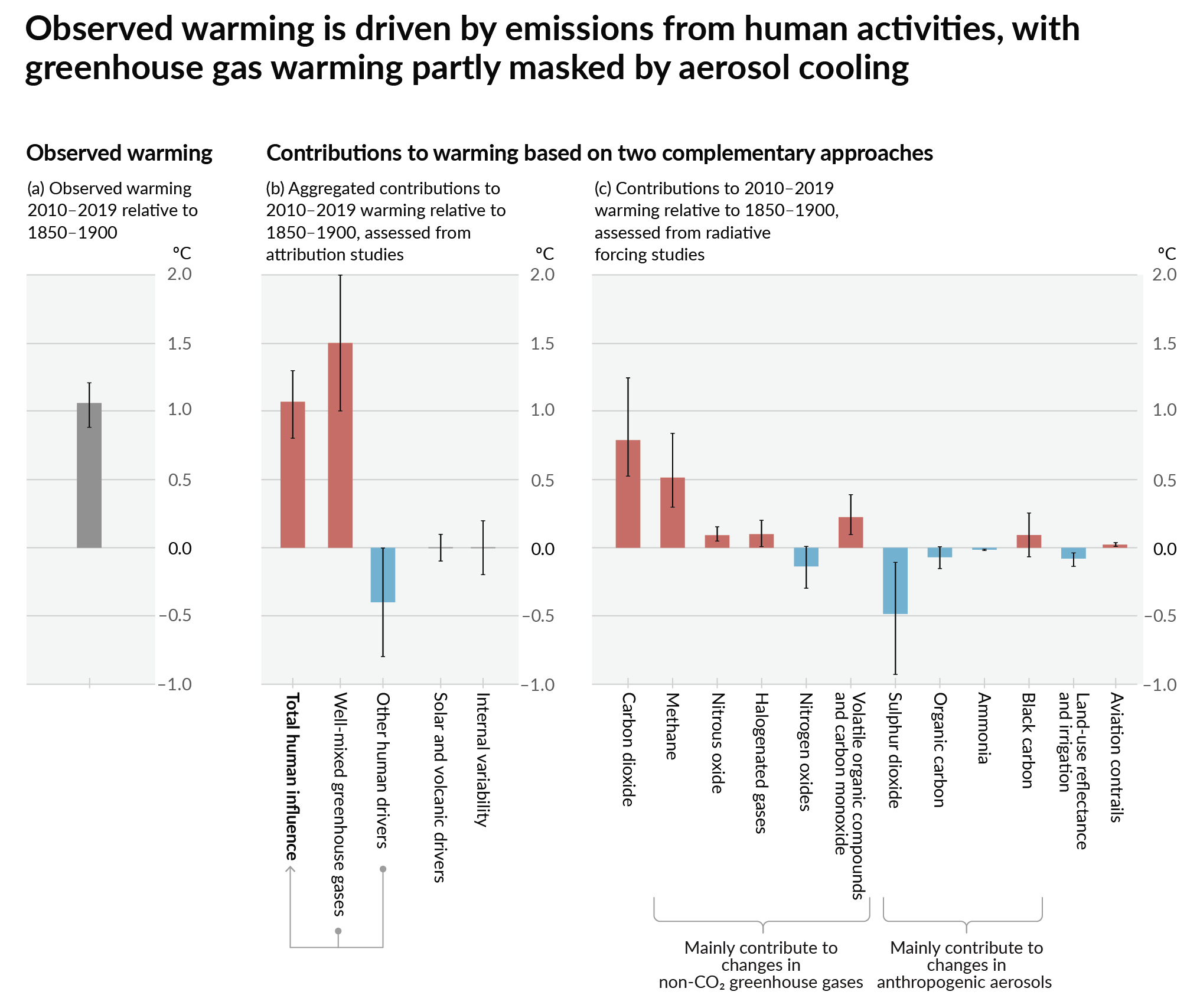

How much each change to the atmosphere has warmed the world:

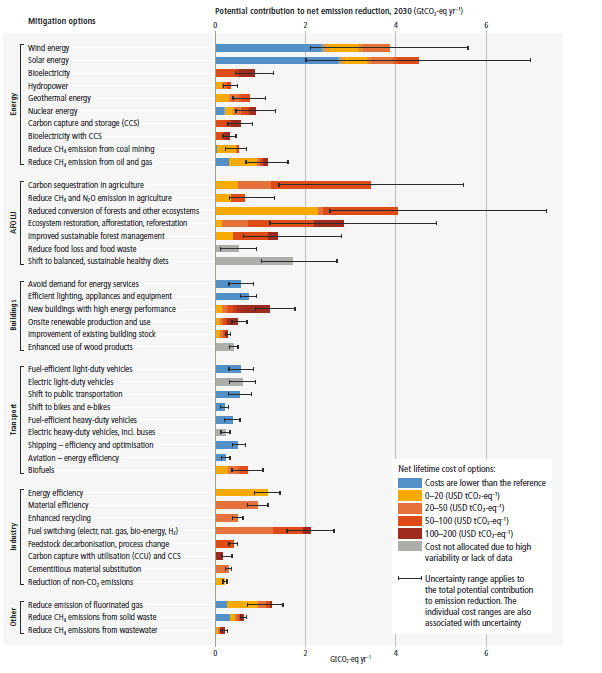

Recommended actions to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the near future:

Anti-science, inactivism, and unsupported conspiracy theories are not ok here.

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

26

118

27

28

29

48

Is vehicle pollution still a problem? Yes, here’s why it still harms health and climate.

(science.feedback.org)

30

31

32

33

34

171

A juice company dumped orange peels in a national park. This is what it looks like today

(www.upworthy.com)

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

14

What Is An Emergency? Thinking as calmly as possible about where we find ourselves

(billmckibben.substack.com)

43

13

The Canadian feds’ new billions for Trans Mountain weren’t a loan, filings show

(www.nationalobserver.com)

44

19

The unique ‘bulky’ attribute of fluorine can actually be replicated in a different, non-toxic form.

(www.techexplorist.com)

45

46

48

49

50

72

‘All other avenues have been exhausted’: Is legal action the only way to save the planet?

(www.theguardian.com)